The Best Roguelite Was Made in Gamemaker

A Roguelite genre masterclass with the lens of game design, but not without an introduction of the genres origin

Hello my fellow players,

First of all, merry christmas to all of you! Best wishes to you and your families during this time.

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve died playing roguelikes roguelites, but actually, from my perspective is one of the main factors behind the state of flow. When the creator achieve that connection where the player doesn’t consciously think that it’s playing a videogame, is when the good design has been implemented.

But why do we keep playing? Isn’t it repetitive? Is not easy to create a good balanced roguelites, if the challenge doesn’t exist your feeling is bored as there is no reward or satisfaction on it, on the other side if the challenge is really high and you barely complete one or two dungeons, you will quite soon by frustration.

But before I introduce you to the videogame behind the headline, let’s shortly have a distinction between Roguelike and Roguelite genres as they could be easily mixed and there isn’t a clear definition around, I always prefer to teach with examples…

let’s go!

Let’s go back to 1980…

To understand recent games design, sometimes is quite important we take our time machine (Internet) and we do some research around the genre we would like to know about.

Rogue is a dungeon crawling videogame by Michael Toy and Glenn Wichman with later contributions by Ken Arnold. Rogue was originally developed around 1980 for Unix-based minicomputer systems as a freely distributed executable.

Toy and Wichman, both students at University of California, Santa Cruz, worked together to create their own text-based game but looked to incorporate elements of procedural generation to create a new experience each time the user played the game.

The main features of a pure rogue are:

Random environment generation

Permadeath

Turn-based

Grid-based

Many years later, commercial games borrowed some roguelike elements (procedural runs + permadeath) but dropped others (like turn/grid) and often added persistent progression, people started using roguelite to distinguish them from the traditional hardcore roguelikes, because yes, they could be somehow frustrating.

Unfortunately…These terms are contested and used inconsistently in stores/tags; roguelike is often used as an umbrella term even for roguelites.

Let me introduce you to Nethack.

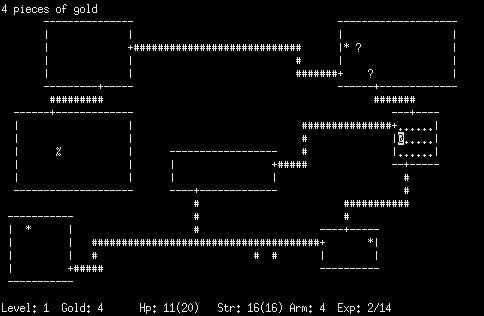

It’s a title I had the chance to play when I wasn’t even a teenager. My uncle introduced me to it, and I completely fell in love with it. NetHack is a fork of the 1984 game Hack, itself inspired by the 1980 game Rogue we just mentioned.

If you think about it, when the videogame industry was in its early “teenage” years (remember Pong released in 1972), good ideas and concepts were already being reused. Today we complain about similarities between new releases, but honestly, I see it as a perk of gamedev: we keep following systems and structures that already work.

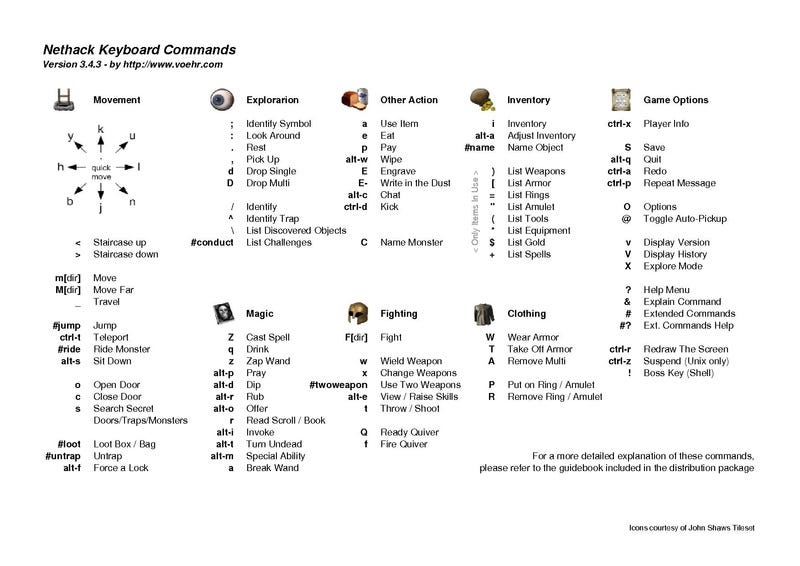

I only played a few seconds as “Jose the Aspirant” (oh—was that a reference to my gamedev journey? haha), and you can see that most actions are commands. Back in the 80s, computers didn’t have plug-and-play controllers like today, so many games were designed with the keyboard in mind.

You can actually play Nethack

Curious Data. NetHack has been inducted into The Museum of Modern Art in New York City, New York, USA (MoMA) as part of their video game collection and is included in the exhibition “Never Alone: Video Games and Other Interactive Design”

Nethack is serious stuff, it is part of history of videogames. If you want to play, be careful as it is addictive. I’m pretty sure games released by From Software take inspiration from this one.

Taking Nethack’s game loop and main features, we can easily understand how this genre is designed these days.

Gamemaker Power Unlocked

It was 17th August, 2016, you can imagine how difficult is to survive the heat on Spain during summer, I remember I was coming back from work, excited to check my usual videogames newsletters and digital stores, then I see an interesting headline on vidaextra.com announcing another Humble Bundle. I bought it immediately, my younger self couldn’t resist the temptation.

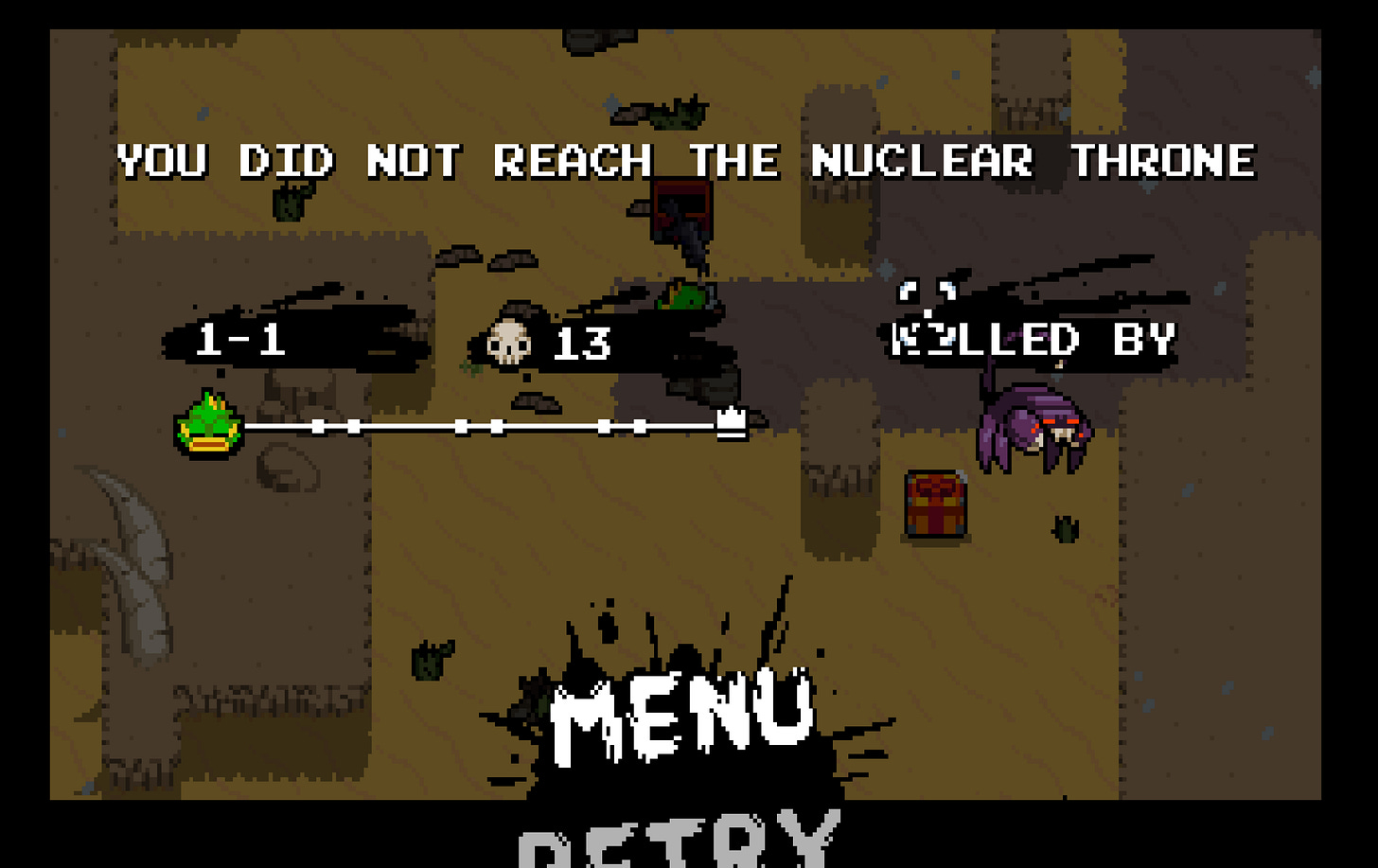

Again, they delivered a masterpiece that’s still part of my DRM-free collection: Nuclear Throne.

I should have hundreds of hours at that game, but unfortunatelly back then when I played it, it wasn’t part of my steam collection so I dont have the real stats.

Nuclear Throne is a near‑perfect case study for roguelites on how to build a brutally replayable game around a tiny core loop, again (you see the pattern?) titles like Enter the gungeon or Voidigo had a strong inspiration from the sensei.

It’s design is exhaustively measured and you can feel that within the first 30 seconds, really well designed games creates a strong magnetism between visuals → input → player.

The initial game feel, the smallest loop you can find, is a orchestra between input and character control → Feedback; move, shoot, character skills. It is just simple and exquisite and I will tell you why, so you run to the Steam Store page. (50% Discount now) 😇

Character Control

No matter which character you choose, all of them feels agile through the map, I’m pretty sure that’s a strong design decision. With fastest movement the exposure to enemies is increased as every step move one entire map tile. (that sounds familiar from nethack, right?)

But that decision was core and as Shigeru Miyamoto would say “A good idea is something that does not solve just one single problem, but rather can solve multiple problems at once”

Fast movement also makes it harder to grab loot (weapons) safely. In many situations, the map is full of enemies and bullets, so you barely have time to read what dropped—you just grab it and move.

Weapons Feel (Gunplay)

Another strong ingredient for the master nuclear throne recipe, the weapons feedback, even just playing with the initial revolver, every bullet feels heavy and huge, so just in a visual way you feel stronger.

Well at least against the smallest enemies as that feeling is going away when you face the first big enemies.

Everytime your bullets or explosive ammo hits an enemy, the feedback from enemies being hitted is another strong design decision, they are not only dying, but they creep with well designed physics through the map.

Yes, dead bodies are visible at the map, so you can feel even stronger.

Enemies

Last but not least: enemy AI.

I haven’t checked the code, but it feels like enemies fall into two main archetypes: aggressive and passive.

Agressive Enemies

When you start your first run, the smallest and weakest enemies always go towards you, but it’s true that they actually move back when you are really close to them, kind of to avoid that bullet from your weapon.

Passive Enemies

When you find stronger enemies, they keep even more distance from you but as bullets never disappear at this game they keep shooting so a some point they will reach you, but they are hidden somewhere so you can’t kill them, they are a real pain.

These two archetypes are part of a connected system that creates a true roguelite bullet-hell experience. Without enemies, moving through the game doesn’t mean anything — it’s that simple.

Wrap Up

Nuclear Throne is not only a very enjoyable roguelite—it’s a masterpiece to study in terms of game design.

Here I focused on the initial game feel loop, but there’s much more: characters with unique skills, cosmetics to unlock, and the higher-level loop where after each biome you choose a mutation that makes your character stronger—changing how the next levels play.

There are many other things I could say about this wonderful game, but you know me: I prefer short articles.

If you’re making prototypes (or even a full game), I think this “first 30 seconds” mindset is a powerful lesson. That first interaction is often more important than the rest of the session—because as humans, we lose engagement over time.

Again, thank you for reading.